1st Study: Validating 'Dutch Reach'

Study finds far hand advantage for Dutch Reach anti dooring method.. See: Validating ‘Dutch Reach’: A Preliminary Evaluation of Far-Hand Door Opening and its Impact on Car Drivers’ Head Movements, Large, DR, et al., Human Factors Research Group, U Nottingham, UK. (PDF). Oct 2018. ICSC 2018 Conference paper.

Dutch Reach Review Article (2017)

Note - April 11, 2020

For a more current and accurate summary about the Dutch Reach far-hand method for safe egress and dooring prevention, see the "Dutch Reach" entry in Wikipedia, As of this date the content is reliable and well documented. It now also notes the global spread, endorsements and instances of official adoption of the reach countermeasure since its coinage and this project went public in September, 2016.

For an overview of the Project itself, its origin, rationale, strategy, execution and results, see the Case Study on the Dutch Reach Project (April 2020) written by DRP and published by the Observatory for Public Sector Innovation of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Note: This paper is posted for public reference and for open review.

The Text on this Permalinked webpage titled "Reach Review Paper" is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. Please inform DutchReach.org if it is posted or printed elsewhere and please provide a copy of the text and web page link using the Contact email address on this website.

Readers are invited to send comments, additions, corrections, with documentation and citations if possible. Please also feel free to suggest additional sources of information for this author to consult and consider for reference and inclusion. Please feel free to circulate this link and paper to experts in the fields of transportation safety, occupational ergonomics, public health, policy etc. Please do not re-post without this full "Note" of two paragraphs and also include the contact email address information for this website and the Dutch Reach Project as appears on the Dutch Reach Contact page, If posted on the web, please provide this link back to this Dutch Reach website and page: (Permalink): https://www.dutchreach.org/?page_id=412

Dutch Reach entry in Wikipedia

Case Study of Dutch Reach Project

Case study on the Dutch Reach Project now published by the Observatory for Public Sector Innovation of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. DRP's case report was submitted in response to OPSI 2020 Call for 'Edge of Government Innovations'. 9 April 2020. Click image to enlarge.

1st Dutch Reach Human Factors Study

7th Int. Cycling Safety Conference presents first scientific look at the Dutch Reach, Oct 10, 2018, Barcelona, Spain. Click here for ICSC site/program.

Dutch Reach Review Article - Contents

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Naming the Unnamed

1.3 Description

1.4 Contemporary Practice and History

1.5 Legal Status of the Reach in Netherlands

1.6 Safety Advantage Considered - Overview

1.7 Safety Advantage Considered - Framework

1.7.1 I: A General Safety Standard for Safe Exiting:

1.7.2 II. Inventory of Evaluation Criteria - Listed

1.8 III. An Inventory of Evaluation Criteria - Applied

1.9 Use Outside the Netherlands

1.10 Recent Awareness

1.11 Anti-Dooring Education & Behavior Change Campaigns

Dutch Reach

1.1 Introduction

The "Dutch Reach" refers to the customary and officially prescribed[1] 'far-hand reach method' used by Dutch drivers and passengers to safely exit their vehicles without endangering self or others.[2][3][4]'Once a strong ingrained habit, the Dutch Reach is as thoughtless and automatic as the near hand habit, but arguably much safer.

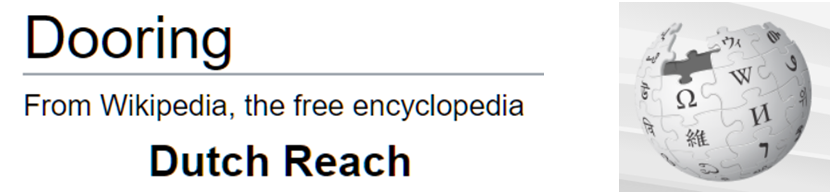

The "Dutch Reach":

Reach across to door with far hand to swivel and look back before and while exiting vehicle.

It is particularly protective of cyclists passing in the door zone, bike lane or corridor along side parallel-parked or stopped cars. For they are at sudden risk of being illegally obstructed[5] or "doored."[6][7][8]from either side. If so blocked, a cyclist may crash into the door or exiting person, be pitched over it or outward into the street or into a tree, post or other hazard,[9], or forced to swerve into traffic or other danger, and thus to suffer grievous injury or death.[10][11]

Urban bicycle safety advocates in the USA, Canada and Australia often rank doorings as the perhaps the single most common bicycle-car collisions[12], more so if non-contact door-avoiding swerve crashes are included. Many such crashes are relatively minor and the victim does not receive nor seek emergency medical care nor reports injury or damages to the police. Hence the incidence of dooring-related crashes is very likely under reported.[13] As doorings are most prevalent in older dense cities with narrow streets, parallel on-street parking, and a growing bicycle presence, national statistic fail to capture this rather localized problem. For given its low fatality rate when diluted nationally, it has for this reason not become a matter of concern for the National Highway Transportation Administration (NHTSA). Nor are the words "doored" or "dooring" recognized when searched in the database of the federally-funded Bicycle and Pedestrian Information Center.[14]

The accompanying diagram depicts its hallmark far hand reach to the door latch which initiates the method. The "Dutch Reach" is demonstrated in the video The Dutch Reach (Safe For Work).

1.2 Naming the Unnamed

In the Netherlands, where the reach method likely originated, the Dutch language lacks a specific word or term to name it. Possible reasons for this namelessness are offered below. The moniker "Dutch Reach" was coined by an American physician in 2016 to specify the method and give it currency through his anti-dooring campaign.[15]

Note: For this article, the terms 'reach', 'Dutch method', ' ~ maneuver', '~ practice', 'reach across' or similar terms will also be used to indicate the "Dutch Reach" -- but usually in its pre-2016 context.

Description

The signature feature of the "Dutch Reach" is use of the far hand for opening and exiting one's car or vehicle, rather than the hand nearer to the door. This choice sets off a series of five linked actions: Reach, Swivel, Look back, Open slowly, then Exit facing traffic. This sequence provides a significant safety advantage to avoid dooring, stepping into traffic, or door collision damage.

Rather than using the hand next to the door itself to open and exit, the Dutch use their far hand. This requires one to reach across his or her chest to operate the latch handle to open the door. Its claimed safety advantage relies on the physical fact that reaching across forces one to swivel the upper torso. This enables one to look out to the rear view mirror, out to the side, and then swing one's head easily back over one's now quarter-turned shoulder, to see on-coming traffic. One first looks back through the window, and then without compromise as one partially opens the door. This allows a continuous view of on-coming traffic while preparing to exit, when further opening the door, and when stepping out.

Such a full, seamless view of approaching bikes and vehicles is not likely -- nor easily possible if at all -- when the near hand is used. The Dutch Reach has other safety advantages as well. Reaching across, one is far less able or likely to fling the door open quickly or widely. Held on the door, the far hand requires one to step out facing out and back. Holding the door with the near hand leads one to step out facing side-ways and toward the front.

Another advantage, the reach method reduces dependence on the outside rear-view mirrors -- which are of course not available to assist back seat passengers. While initially valuable, mirror views are often compromised, and quickly deflected and lost the moment one shifts one's head and angle of reflection. If the mirror is misaligned to start, rain-marked, clouded, tinted or missing, the view back is lost or degraded, and blind-'spot' sectors increase. In the dark, mirror use may also be more problematic than direct sighting; headlight or solar glare may also be an issue.

With the Dutch Reach, the swivel encourages a quick look back with the outside mirror. But swiveling back around, one looks directly back first through the side windows, then through the partially opened door. The near hand user, should they choose at all or by habit rely on the mirror view for sighting back, may overly rely on its partial scope and time-limited view.

From the back seat, passengers have no mirror to help exit at all, unless perhaps the inside rear-view mirror which in most instances would be useless. Not surprisingly, it is not uncommon to find some rear passengers instinctively adopt a far-hand assisted swivel and peek method before opening and exiting from the back.

For more, see below, "Safety Advantage Considered".

1.4 Contemporary Practice and History

The reach is believed to be a common though not universal practice in the Netherlands. Polling or research on this question is not presently known ever to have been performed. According to one Dutch transportation safety authority in the Netherlands, "The right-handed reach-to-open method used by Dutch drivers, has been done this way for at least 50 years. It has no specific ‘inventor’ or origin story, but emerged in this bike-friendly country as our preferred commonsense practice."

Documentation of its invention, if to be considered such, apparently has yet to be sought by Dutch sociahistorians and safe roads specialists. Visiting journalists, transportation safety experts and cycling advocates and tourists have been briefed by guides and authorities on the method and duly reported it back home. -- though others including some foreign expatriates report never witnessing nor being informed of the habit. But whatever its actual extent, its use contributes to the safe co-existence of multiple modes of road use.

Again, as best thus far known, little has been made among the Dutch of this relatively unique car door opening practice. It has been claimed, but also disputed, that the Dutch use it widely and habitually from childhood on. Informal but effective inter-generational transmission of the method among those who favor has been described, and reasonable to believe. For even while watching from car seats, toddlers may learn it as they see their parents and siblings use the habit. It is also reported to be taught in school -- or not, for licensed Dutch drivers in Holland and abroad again differ on this question. However it does seeim probable that now as Dutch road culture, traffic code, driver trainign, licensing examinations, and infrastructural reforms since the 1970’s have vastly reduced all traffic-related deaths including doorings, and with it the practice may have waned

Reports have differed on whether ithe reach across move is written into the Dutch traffic code or required on the driver licensing examination. In fact NL traffic law does not specify the far hand reach method, But the code for safe exiting and the official licensing exam are so strict on the issue of safe exiting after parking, that the far hand method has been regarded, and taught by driving instructors as the best way to assure student drivers pass the licensing exam. It is that practical imperitive which led many to believe that the code specifies the reach. But here to, it may no longer be as much demanded by road test examiners.

While the instruction for drivers to use the right hand is taught as proper practice by instructors,i t is also conceded that the reach is not the only way to pass the over-arching safe exiting requirement which informs the code. Research or polling to clarify the present day prevalence of the reach in actual practice, or in driver training and testing has not been reported if performed, or not yet found in English. This writer is not in a position to judge the diverse hearsay, and scholars and experts on Dutch driving culture are encouraged to weigh in. For perspective, it is worth noting in passing that the Dutch system of driver education and licensing is said to be most rigorous and thorough, far more so than in any of the United States' numerous licensing jurisdictions.

While the reach's origin five decades or so ago is vague, lost or mythical, its legislative history should be retrievable from the official record. Furthermore, past press coverage contemporary to that legislative advance may also shed light on the social forces and context which led to its present codification. Given its suggested age, the emergence of the "reach" practice may possibly be related to the "Stop de Kindermoord" protests (literally "Stop the Child Murder") which erupted in the early 1970's.[19] At that time, increased motor vehicle ownership and use presented an alarming danger to bicyclists and pedestrians. 450 child deaths were reported in 1973.[20] The protests led to significant road safety legislation, planning and practices leading to the safer and friendly bike/ped/motor co-existence in the Netherlands which today is internationally studied and lauded.

Within Holland, while some doorings still occur, this apparently has not prompted sufficient concern to provoke any modern anti-dooring campaigns. Dutch instructional [videos] which include the reach method do exist. However no examples of Dutch public educational, outreach and behavior change campaign materials for the reach method have thus far surfaced, had they once existed. It should be recognized that the Netherland's extraordinarily low incidence of bicycle crashes,[21] doorings included, reflects the introduction of numerous and extensive infrastructural, behavioral, legal and social changes since 1971 which permitted and encouraged the growth of bicycle use and a 'virtuous circle' of regard for cycling and cyclist safety.

Allegedly now considered a commonplace in Holland and doorings there now a rarity, the Dutch accordingly pay the reach scant attention. As noted above already, its nameless and invisible use in Holland is understandable. But this has prevented its travel and export elsewhere. Hence it apparently has remained unseen, unspoken, and largely unknown outside of the Netherlands (Belgium, Denmark or other nearby European states may be exceptions here). This nameless-ness is thus both a manifestation and cause of why the reach remains difficult to trace or track, or find by typical search and retrieval methods for reporting or research purposes.

1.5 Legal Status of the Reach in Netherlands

As provided and explained by a transportation professional affiliated with CROW in the Netherlands:

"Presently, there are two rules that are specific about opening vehicle doors:

Article 4 e[22] says:

het permanent rekening te houden met (mogelijke) andere weggebruikers, in het bijzonder kwetsbare weggebruikers als voetgangers, fietsers e.d; [translated: to take permanently into consideration (possible) other road users, special vulnerable road users such as pedestrians,bicyclists, etc.]

And Article 6a says that you are specific tested on:

het op juiste en veilige wijze in- of uitstappen; (translated: getting in and out of the car in a safe way

On the website about car driving instruction the method for safe exiting is specified.[23] "This way of getting out of the car is the standard in driving instruction:

Handelen bij uitstappen en weglopen van de auto: 1. pak de handgreep van het portier vast met je linker hand. Houd de handgreep vast zodat losrukken door de wind later bij het ontgrendelen (3) voorkomen wordt 2. kijk vóór de auto, in de binnenspiegel, de linker buitenspiegel en over je linker schouder om te oordelen of je veilig en zonder het overige verkeer te hinderen uit kunt stappen 3. ontgrendel het portier met de rechterhand, terwijl je de deurgreep met links blijft vasthouden Door deze volgorde aan te houden bevorder je een juist kijkgedrag. Je lichaam moet je op deze wijze al een kwart naar links draaien, waardoor het kijken over je linkerschouder en naast de auto een automatisme wordt

[Translated: 1. Grab the grip/hold of the door with your left hand. Hold the handle in order to prevent tugging the door by the wind when unlocking 2. Look in front of the car, in the inside mirror, the left outside mirror and over your left shoulder if you can get off the car without disturbing the other traffic 3. Unlock the door with your RIGHT HAND, holding the door grip with your left hand. By following this sequence you encourage the correct way of watching. Your body should make a quarter turn, ensuring that looking over your left shoulder alongside the car becomes an automatism.]

Not all Dutch Far Hand Reach advantages are obvious. 10 reasons are given above (click to enlarge). A more thorough explanation is given here.

1.6 Safety Advantage Considered - Overview

As a public safety intervention, any claim that the Reach method is safer than its near-hand alternative rests largely, if not entirely, on practical thinking: That one is more likely to avoid injury to self, others, or door damage, if one sees - or hears - rapid on-coming traffic before irrevocable action.

For as of this writing it appears that no research has ever been conducted or published in the Netherlands nor elsewhere to evaluate the intrinsic or public safety value of the far hand reach method. Absent simulation or epidemiological studies, decades ago Dutch 'commonsense' deemed the Reach the safer, more sensible alternative. They went on to adopt it widely by social consensus and peer encouragement. If there was disagreement or debate on this choice, the record is currently blank.

Whether future studies might one day challenge the Dutch endorsement remains to be seen. Meanwhile, that approval is but an 'argument by authority.' Yet that authority cannot be ignored given what Holland has accomplished over the past half century in road sharing safety. So their endorsement is for many quite persuasive, more so when taken together with the Reach's obvious and practical line-of-sight advantage.

In the absence of research, one may conduct a 'thought experiment.'[24] That is, to assess merit by means of an analytic comparison and evaluation of each method as considered in thought and observed in practice. By systematic examination of exiting methods against criteria for safety one may compare and contrast their likely safety value and provide a reasonable basis to judge their respective merits and short-comings. Such an exercise will not settle the question but may clarify issues and provide a reasonable basis for opinion. Such an examination follows in Part II.

1.7.1. Safety Advantage Considered - Framework

Presented here -- with an attempt or pretense of objectivity -- is an analytical comparison, a thought experiment, intended to help discern the relative safety value of the alternatively 'handed' methods. This study will proceed as follows:

I. A general standard to interrogate each method for safety value for exiting is given:

Question: Which is the safer baseline habitual method: The 'near-hand push' or the 'far-hand reach' method?

II. An Inventory of Eleven Evaluative Criteria is presented.

The general standard is now subdivided into a set of eleven specific, functional criteria for examining the safety value of each method:

An optimal safe exiting method - specifically and functionally - would:

1) Provide, and optimally necessitate, maximal awareness [by exiting driver/passenger] in space and time of on-coming traffic.

2) Prevent or minimize pre-mature, risky or irrevocable and dangerous actions.

3) Be simple, easy, and natural to perform.

4) Be simple and easy to teach, learn and habituate.

5) Be effective and appropriate for adults and children, drivers and passengers.

6) Be free of intrinsic physical strain or injury to users when performed.

7) Be a reliably autonomous action resilient to parts defects, absence, and limitations.

8) Habitually ensure safety when under stress, inattentive or otherwise compromised.

9) Be a necessary result of a necessary action.

10) Be protective under adverse environmental conditions: light, weather, roadway, traffic, and vehicle location.

11) Other safety considerations - emergency exit, etc.

III. The Inventory of Eleven Evaluative Criteria Are Applied:

The alternative methods will be examined for safety value under each specified criteria.

How well does the method allow, promote and/or assure seeing oncoming traffic, a) in space, b) over time, c) and under substandard states of operator, equipment or environment? And as observed in practice, how well is it precautionary, protective, and fail-safe for each party?

An optimal safe exiting method specifically and functionally would:

1) Provide, and optimally necessitate, maximal awareness [by exiting driver/passenger] in space and time of on-coming traffic.

Direct View

The far hand reach method naturally forces a quarter turn swivel of shoulders and head outward, allowing natural view of outside rear view mirror, then and out to the side, and then permits easy further rotation of shoulders and head to look directly back toward on-coming traffic. View is not overly confined to or dependent on mirror, and a near 180° survey of the road front to back may be achieved. Use of the rear view outside mirror is not obligatory but one's gaze would pass to it during the swivel motion, and may be consulted. With far hand on opening door, one exits facing side-wise or directly back, maintaining continuous view of on-coming traffic as one chooses to open the door, only opening more fully and stepping out when safe to do so, or to pull back in and retreat if not.

The near hand push method does not require nor encourage a shoulder or head turn, though it may be voluntarily performed or habitual for many drivers and passengers. With near hand fixed on handle or door rest, near upper arm and shoulder are fixed as well, impeding and discouraging shoulder and head rotation beyond ~ 90° - 120° out sideways and partially back. Direct gaze backward is strained if not impossible, and unlikely to be performed by most.

Mirror View

To help assure safety, drivers and front seat passengers may, and should, use respective outside rear view mirrors (wing mirror) to look back for on-coming traffic. But in real world behavior, such use is not obligatory, physically necessitated, nor reliably performed, though it is voluntary or habitual for many.

Important as it may be in the initial phase preparatory to door opening, mirror use and dependence upon it for seeing back entails some potential and some unavoidable short-comings. Such limitations are a function of a mirror's optical qualities (eg. planar, convex, aspheric), positioning whether on the car body or door frame itself (in which case it moves with door opening), user sight-line, behavior and time of use. These factors affect the mirrored field of vision, and the time such visual information is valid and observable. It applies to both the near and far hand methods, although as has been noted, the far hand method allows and encourages direct sight to take over if the mirror view is neglected or by necessity lost as exiting proceeds.

The near hand method, if the mirror is even used, does not afford such easily achieved direct vision back to guard against on-coming danger. In the case of the far hand method, one is less disadvantaged if one neglects to the check the outside mirror as a direct view back is easily available before door opening proceeds.

Mirror features, placement, adjustment, and qualities vary considerably. High end side rear-view mirrors may provide split mirrors and fish-eye curvature to overcome blind sectors, with and without distorting perceived distances. Mirrors may not be properly adjusted by the driver, and even when done, the passenger side mirror will serve the driver, but less so the front passenger who might wish to use it to aid exiting.

User line-of-sight is most variable as shift in head/eye-angle-to-mirror immediately shifts the view reflected, whether to greater advantage, or loss which makes the mirrored view useless. Hence time-of-use limitation is unavoidable. Useful mirrored view is lost once one rises, turns head or swivels to assume another position in the looking, opening and exiting sequence. Unless the user can quickly replace the mirrored view with direct sight, the operator is acting on expired information. This may even prompt one to hasten one's door opening and exit, to step out quickly before the scene back changes or a distantly perceived cyclist or vehicle arrives.

Other mirror issues may seriously affect safety in exiting: Rear seated passengers are not provided with rear-view side mirrors, and must make do entirely without their temporary benefit. Front side mirrors may be defective, improperly positioned, or variously compromised for viewing by darkness, approaching headlights, grime, rain, snow, ice, as well as inherent blind spots.

2) Prevent or minimize pre-mature, risky or irrevocable and dangerous actions.

As noted above in 1), the reach method favors a direct and continuous view of on-coming traffic, allowing a more fully-informed judgment compared to the near hand method. Hence pre-mature and risky action to open the door, open it quickly, or throw it fully open unaware of immediate risks in space and time, is more liable to occur, particularly with less conscientious agents. Habituated reach users need not be so consciously conscientious, as their reach automatically positions them to see on-coming vehicle risk regardless. One is then more capable of stopping or aborting dangerous actions.

In addition, as yet not remarked, the act of physically reaching across with one's far hand and arm significantly reduces the force and speed with which one might push open the door into traffic. One's hand and arm cannot effectively extend or push as hard as a near hand and arm often can, and does. Hence, should one prematurely start to open the door, it will likely only open partially and slowly. This will give on-coming cyclists and vehicles early warning before full opening and thus time to react more safely. Partial opening also allows greater room for safe passage, reducing the risk that cyclists need swerve at all. Or if a swerve is provoked, the cyclist may swerve to a lesser extent. His/her risk may then also be reduced for being struck directly by a vehicle traveling adjacent, or for losing control and crashing to pavement, be injured, or again, struck by on-coming traffic.

The above advantages are not inherent for near hand users. A near hand user as already described, lacks an assured continuous view of on-coming traffic, and what view he/she has is inherently compromised over time and line of sight. The near hand user is can more easily and will on occasion fling a car door fully open preparatory to exiting, with no necessity to view, with no capacity to retrieve a widely and blindly flung door. Whereas partial, slower opening is a consequence and virtue of the reach, this inherent (and unintended) protective advantage is lacking for near hand users.

3) Be simple, easy, natural to perform.

Both the near and reach methods are simple, easy, and natural, and can become habitual to perform. That the international consensus appears to favor the near hand may signify that by these measures it is physically and energetically advantageous. Add to this explanation the obviousness of using a near hand to perform a near action, with force and speed, the case would seem made, but for safety. Yet the Dutch have found the reach too can be popular and also habitual.

4) Be simple and easy to teach, learn and habituate.

The use of a near hand for near action is itself simple, easy and not at all in need of teaching or training learning. Though here again, the Dutch in practice achieve transmission of the practice with, it is claimed, minimal effort or fuss though inter-generational transmission from toddler-hood on, by monkey-see, monkey-do. Late adopters do indeed need to retrain, substituting one habit for another. How well older dogs can learn new monkey tricks remains to be tested on a wide scale. But the teaching and learning is less the problem than embedding it as a compulsive habit in new practitioners. Progression to general habitual use would likely proceed most easily starting with the young.

5) Be effective and appropriate for adults and children, drivers and passengers.

Both methods can be performed from all positions by all able age groups. Body size, build and bulk, strength and flexibility may affect competence and qualities of performance. The physically compromised may find the reach more difficult than the near hand method.

Significantly, however, the absence of a rear view side mirror presents a safety disadvantage for rear-seated passengers who rely on the near hand method. For as in the front, their fixed near hand, arm and shoulder hems them in and blocks a fuller turn to look out and back. Lacking the a mirror, too troublesome or difficult to contort and try to see, they may open the door without full sight or awareness of on-coming traffic.

Use of the far hand reach mitigates these problems. It affords the same advantages from the back seat as from the front seat, minus the optional glance in the mirror. For with the reach, the mirror provides a initial but minor assist, given the swivel and direct sight line back which the reach facilitates.

6) Be free of intrinsic physical strain or injury to users when performed.

Using the near hand and arm to open and exit creates specific physical impediments to safety: A near arm and hand fixed on the door blocks the outer shoulder from rotating, making it awkward if not impractical to turn one's head further back to gain a full view of on-coming traffic. As noted previously, the far hand reach naturally causes the outer, near door shoulder to rotate back, allowing and encouraging the head to turn further to provide such a direct view of on-coming cyclists and other traffic.

Neither method would appear to be injurious for a normally fit and sized person. But individuals with arthritis or stiffness, excessive body bulk or size, or lack of flexibility, short arm length or strength may find the reach maneuver challenging, impractical or impossible. The near hand method would not present similar difficulties. On the other hand, the different method may prove easier or more physically favorable depending on underlying personal conditions. For example, some with back problems may find one method reduces or increases strain to vulnerable joints or weakened limbs.

Dutch Reach Review Article - draft 10/16/16

7) Be a reliably autonomous action resilient to parts defects, absence, and limitations.

Both the near and far hand methods are regularly performed by myriad drivers and passengers multiple times each day. And to the extent they do not depend on others or external aids they are autonomous. Supplementary equipment such as side rear-view mirrors, bicycle detection sensors (e.g. radar)[25] [26]to alert drivers, 'door opening!' outside lights which flash when seat belts are unbuckled[27], or lights exposed in the opening edge of the door itself better to warn approaching cyclists and vehicles, etc. when present and functioning correctly can and do increase safety when exiting. But at the same time they decrease autonomous reliability by the person exiting. The cabin signal must be on and heeded, external lights depend on being seen and understood by others. Likewise as discussed above, in the case of mirror reliance, all things being equal the far hand method is inherently more reliably autonomous when compared to the near hand method which relies more on a functioning aligned mirror being present to improve safety.

8) Habitually ensure safety when under stress, inattentive or otherwise compromised.

Occupational safety professionals recognize that "People are as likely to fall back on a positive habit as a negative one. In a safety context, improving workers’ behavioral baseline will make them safer when they are most at risk."[28] Beyond engineering safe vehicles, infrastructure and traffic regulations, a major key to safe driving is to adopt safer habits.[29]

Both the near and far hand methods are usually routine, habituated actions, long performed and frequently repeated to the point of automatic action. They are available and enacted often free of conscious decision, variation or modification. Such a habit can be good or bad depending on its inherent safety and immediate context. But a poor habit may always provide a poor baseline for behavior, while a good habit will likely be beneficial and fail-safe. When a person is mentally or emotionally compromised --tired, stressed, inattentive, under the influence, emotionally charged or otherwise heedless or impulsive -- poorer performance of any activity can be expected, at times with serious consequences. Safer baseline habits defend against such lapses. Reliable and fail-safe habit is to be preferred over poorer habits. As the far hand habit allows a reliable and real time view of on-coming traffic, and inhibits wide and fast door opening, it provides a better baseline and fail-safe habit than a near hand habit.

9) Be a necessary result of a necessary action.

Experts recommend that where possible, behaviors be structured or designed to guide or compel agents to perform procedures the safest way.[30] Safety is to be engineered into the activity. A linked chain of preferred motions should be initiated which eliminate hazardous links downstream.[31]

A preferred safe method should be as unavoidable as possible, and as such safety is necessarily aspect or result of the required activity. The a chained sequence, along with habit, channels safer behavior. The more ways an action can deviate from the intended sequence, the less fail-safe it is.

In this regard, the far hand habit limits initial door opening even when passion or impulse rule, and positions the person to turn facing the on-coming traffic as they prepare to and do step out. The near hand habit allows the near hand and arm to more readily push and throw open the door earlier, wider and faster should the person allow impulse to overwhelm judgment. While both habits may fail to consult the mirror, the lack is less critical for the far hand user who easily gains a direct line of sight.

10) Be protective under adverse environmental conditions: light, weather, roadway, traffic, and vehicle location.

Adverse contexts due to natural environment, road way and traffic conditions may also affect the estimated safety value of each method. The Mirror View in section 1) above includes discussion of weather impacts on its use.

Strong wind is another concern. Wind can catch a partial or fully-opened door and make it difficult to control or retract. A far-hand reach results in a more cautious, partial initial door opening, which can prevent a the door from catching too much wind, and signal the need to maintain tighter control of the door. The near hand method permits, and its more prone to faster and wider initial or even completely flung opening. As such it would be more likely to catch the wind and be soon fully and forcefully extended. Wind from the front poses an opposite situation. Then the occupant may require considerable force for opening against wind pressure. The near hand and arm could then be required. But this need would not likely put safety at issue.

Road and traffic conditions, such as exiting on a blind curve or amid heavy traffic would appear to favor great caution. The mirror view may not register a vehicle turning into a road or around a curve. It may be that the best method would favor a wide-angle direct view, through all available windows, followed by cautious partial opening and partial exit with as wide a rear view as practical. Again, the far hand method favors the direct view back from inside and out. Mirrors and rear-view mirrors are available for both techniques, but time delays after use again reduces their value when needed most.

It should not be forgotten that whenever possible passengers should exit to the curb, sidewalk, or side of road. But even there, cyclists, skate-boarders, joggers as well as blind, smart-phone blinded or otherwise inattentive pedestrians present risk of collision and injury. But greater danger is still to be had for and by passengers exiting into traffic.

Doorings from the passenger side into the bike lane, or The Uber/Lyft Effect[32], is increasingly a concern in cities across the globe. The risk is greater than that usually posed by identifiably marked and professionally operated taxis. For ride-shares are unmarked, loosely unregulated if at all, with non-professional drivers who let or cannot prevent pre-paid customers from jumping out in mid-stream when traffic is paused.[33] It highlights the need for passengers as well as drivers to exercise much greater caution when exiting.[34]

Such passengers open doors directly into the bike lane, corridor or door zone, and put cyclists and themselves at particular risk. Cyclists wary of dooring from parked cars ride at the outer margin of the door zone or at the side of the traffic lane to keep a protective distance. They scan for dooring risk from the parked side. Cyclists have both physical and attentional difficulty attending simultaneously to the opposite, traffic lane side as well as to the parked side. And they always must attempt vigilant attention to navigating the road, for signals and signage, road bed defects, pedestrians, other cyclists, traffic flow, entering and turning vehicles etc. As back seat passengers lack rear-view mirrors to consult, and in many cases the configuration of the rear seat and frame opening, present unique constraints for exiting, all exits from such location is ill-considered. But dropping off in the midst of traffic, impatient and disregardful of the risks posed to begin with, such individuals are also most likely to try and be quick about it -- as they are blocking traffic -- and open the door more suddenly and widely to get out and away.

Again here for reasons already detailed above, the near hand method with its lack of a mirror for back seat passengers as well, appears the less protective than the Dutch Reach. For the near hand allows faster, wider opening and interferes with achieving a full direct view back at on-coming cyclists before full opening and when stepping out.

11) Other safety considerations - emergency exit, etc.

Apart from safety value to prevent collisions when exiting, other risks require additional criteria for consideration. Rapid and safer exit from a vehicle under emergency conditions may, depending on context, suggest different choices. If rapidity is valued above all else , the near hand method which permits fast, forceful and wide opening could prove advantageous. If not the sole consideration, then risk of on-coming traffic would conflict with the risk of remaining inside slightly longer while at risk of fire, explosion, secondary collisions, car-jacking or abduction. It may be argued that it is under such stress that baseline safe habits are a most valuable safety check. But emergency arousal could well preclude conscious choice or over-ride force of habit, for good or ill.

Dutch Reach Review Article - draft 10/16/16

1.9 Use Outside the Netherlands

At this writing it is unknown in which countries and to what extent the Reach may be in habitual practice. Recent anecdotal reports and speculation suggest it may be found in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France and Sweden, but confirmation and knowledge of distribution and extent of use remains to be determined. Lack of known search terms and the Babel of language barriers, make even an informal survey difficult.

Explanation for the apparent absence of international awareness or practice of the reach method may be attributable to several factors: language barriers; lack of a name to translate, reference and share; lack of Dutch emissarial promotion; and the method's own modest, commonsense, and commonplace invisibility have likely made it easy to miss, neglect and under value. One may add to this the lack of material, web, words or images, research interest, inclusion in academic and public policy conferences, nor dedicated advocates or organizations working to facilitate its transmission across cultures and boarders.

It is not presumptuous to assume that the reach habit is currently practiced only in a few European states beyond the Netherlands, if that. Anecdotal reports suggest it is informally used to some extent in Denmark, Belgium, France and Germany. For the absence of positive reports elsewhere, and anecdotal reports of surprise when even transportation safety professionals elsewhere are informed the Dutch open doors differently, does suggest absence of use in those countries.

Of the English-speaking world as represented on the web more is knowable. Almost no evidence has surfaced to indicate that any nation in the English language web community -- Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, United Kingdom, former and current Commonwealth nations, the United States of America or beyond -- practices the reach method to any significant extent. This is inferred from web search, and both by presence and absence of reference to the Dutch alternative in anti-dooring campaigns. Absence of mention of the Dutch alternative strongly suggests the near hand push habit is dominant if not entirely the case.

This writer phoned and questioned dozens of prominent bicycle organizations across the USA during the summer of 2016. He found the reach method was new information to many who ought be most expected to know. But for San Francisco (and in Canada, Montreal) -- no other major group contacted had included the reach method in its educational outreach efforts, let alone their advocacy agenda.

The Montreal Bicycle Coalition recommended the reach method during its 2014 anti-dooring campaign launch.[35][36] Its slogan, graphics and messaging -- "Une Porte, Une Vie"[37][38] -- is a call for increased vigilance and caution, rather than bringing the reach method into general practice.

In 2015 the City of San Francisco, CA, USA, in collaboration with the SF Bicycle Coalition and Vision Zero - SF produced a large vehicle urban driver training safety video[[1]] with what may be the first English language video demonstration of the method.

Otherwise, to this writer, up until September 2016, the web record appears blank.

1.10 Recent Awareness

The term "Dutch Reach" was coined by an American physician and cyclist in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA the summer of 2016[39] to brand and introduce the practice into urban road safety culture. The name was devised to provide a suitable term to identify, discuss, study and promote the method to reduce doorings and 'near doored' encounters between cyclists and vehicle users, as well as to protect discharging occupants and their vehicle doors from collision.

Prior to September, 24, 2016 references in English to the method on the web, in cycling and bike/ped/car/transportation safety 'content' and scholarship are scant if not only un-find-able. For reasons already stated, it has lacked a name and defining identity - and as of this writing it likely still lacks a Dutch moniker, unless the Dutch now adopt the American suggestion.

The earliest English-language web report of the reach habit found thus far dates to July, 2011. No scholarship or anti-dooring campaign in the English speaking world has yet been identified which specifically or substantially mentions, investigates or promotes the Dutch method as a recommended behavioral response to dooring risk. However the Montreal Bicycle Coalition's "Une porte, Une Vie" anti-dooring campaign of 2014 does (as noted above) include verbal description of the reach method during several TV news interviews. Soon after in 2015, the City of San Francisco, CA, USA's SFMTA in partnership with San Francisco Bicycle Coalition and Vision Zero - SF produced a safety training video for large truck urban drivers which includes a brief demonstration of the method.[40]

Shortly after "Dutch Reach" first appeared in print, an outdoor online sports magazine produced a short, faux risque video for social media -- The Dutch Reach: (Safe For Work)[41] -- which in its second half accurately instructs and demonstrates the reach. Within three weeks via multiple portals the video garnered over 500,000 views primarily in North America but on other continents as well. Together with other portals and coverage, knowledge if not actual practice of the method is now being disseminated to 'Dutch Reach-naive' populations'.

1.11 Anti-Dooring Education & Behavior Change Campaigns

In Australia (Victoria, Melbourne), Canad1.11 Anti-Dooring Education & Behavior Change Campaignsa (Montreal, Toronto), the UK (London) and USA (Boston MA, Chicago IL, Fort Collins CO, New York City NY, Portland OR, Seattle WA) bicycle and dooring awareness campaigns -- usually launched by cycling organizations -- have sought to heighten driver vigilance and caution when exiting their vehicles. Cyclists as well have been alerted to the danger and how to reduce their own risk. Stickers, window and mirror decals, social media videos and other marketing campaign elements are typically deployed. To date, no campaign has specifically focused on persuading all drivers and passengers to replace their 'normal' near hand habit with the far handed 'Reach.' A gallery of anti-dooring campaign stickers, signage, research and related materials may be found here

This article is under construction. All reference material for claims above may be found at www.DutchReach.org, including early media reports in 2011 & 2013, and the Dutch statues and a list of FAQs's based on a Dutch transport expert at CROW.NL Full disclosure, I am the originator of the coined term "Dutch Reach" as first reported by Steve Annear of the Boston Globe article of 9/8, 2016 , and subsequently cited elsewhere eg. Outside Online, 9/21, WGBH - PRI/BBC World Service: The World, 9/27/16 coverage, website creator, and indirect instigator of the first English social media video devoted to the reach practice, and now widely accessible on the web at various portals with over 800 hundred thousand views since 9/21/2016. [42][43]

CITATIONS

Jump up ^ http://www.autorij-instructie.nl/2010/02/handelen-de-lesauto-instappen-en-uitstappen/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://nudges.org/2011/08/17/how-the-dutch-watch-out-for-cyclists/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/opinion/sunday/the-dutch-way-bicycles-and-fresh-bread.html?_r=0. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/28/on-dooring-of-bicyclists-and-experts-fees/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://bikeleague.org/content/bike-law-u-dooring. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ {{< Cite web|url=http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/28/on-dooring-of-bicyclists-and-experts-fees/}}

Jump up ^ http://www.bikexprt.com/bikepol/facil/lanes/dooring.htm. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5wBLbUU6lM. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2016/09/02/toronto-cyclist-hit-by-door-video_n_11839504.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://bicyclesafe.com/doorprize.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://chi.streetsblog.org/tag/dooring/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ Empty citation (help)

Jump up ^ http://floridacyclinglaw.com/blog/archives/bicycling-door-zone. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.pedbikeinfo.org/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2013/09/21/bicycling-dutch-way/kFRT0ABSPtUnXMIUj5zONM/story.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0015600/2013-12-31. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ %5d http://www.autorij-instructie.nl/2010/02/handelen-de-lesauto-instappen-en-uitstappen/ ] Check |url= value (help). Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHUh8NCbv_k. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://lcc.org.uk/pages/holland-in-the-1970s. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.aviewfromthecyclepath.com/2011/01/stop-child-murder.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.sharetheroad.ca/what-are-the-dangers-in-terms-of-cycling-safety--p128277. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0015600/2013-12-31. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ {{Cite web|url=http://www.autorij-instructie.nl/2010/02/handelen-de-lesauto-instappen-en-uitstappen/

Jump up ^ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/thought-experiment/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ {{Cite web|url=https://www.bicyclenetwork.com.au/general/policy-and-campaigns/2566/}

Jump up ^ http://www.bikeradar.com/us/commuting/news/article/could-this-invention-stop-car-doors-taking-out-cyclists-45808/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.cyclingweekly.co.uk/news/product-news/will-this-anti-dooring-system-keep-cyclists-safer-on-the-roads-201744. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://safestart.app.box.com/v/habit-of-safety. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ (PDF) http://www.thehartford.com/sites/thehartford/files/safe-driving-habit.pdf. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.asse.org/professional-safety/best-practices/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ Empty citation (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.bikeforums.net/advocacy-safety/1031760-uber-lyft-effect-getting-doored-passenger-side.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.arlnow.com/2015/03/24/bicyclist-doored-by-uber-passenger-in-rosslyn/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://bikeportland.org/2016/03/17/city-now-issues-anti-dooring-window-decals-to-taxi-uber-and-lyft-operators-178090. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ media interviews http://globalnews.ca/news/1252825/cyclists-launch-campaign-to-prevent-dooring/?iframe=true&preview=true media interviews Check |url= value (help). Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/dooring-dangers-cyclists-drivers-need-to-be-alert-as-peak-cycle-season-arrives-1.1804724. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://pt-br.facebook.com/events/1506518232909197/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://coalitionvelomontreal.org/evenements/lancement-de-campagne-une-porte-une-vie/. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/09/08/this-cyclist-wants-drivers-dutch-reach/V2Ei5bEiOCfU6ubxX1r8VN/story.html. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LbC3FQeZqc. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ http://www.outsideonline.com/2115116/dutch-reach. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www.dutchreach.org/?page_id=77. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Jump up ^ https://www. Check |url= value (help). Missing or empty

This page was last modified on 14 October 2016, at 13:23.

The above Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.